By Kristina Moskalenko (Originally published in Kommersant in 2016)

From 13 to 18 June, Ascot transforms into the glittering heart of Britain’s social season for the legendary Royal Ascot. Across the nation, hats are donned with flair and bets placed with eager anticipation, all under the watchful eyes of tradition. Winners are crowned with trophies personally presented by Queen Elizabeth II, each a masterwork by Garrard, the world’s oldest jeweller, whose historic London Albemarle Street salon has been synonymous with royal craftsmanship for centuries.

Albemarle Street holds the distinction of being Europe’s first one-way street. It acquired this status in 1911, coinciding with the arrival of Garrard, the venerable jeweller. Next door, the Royal Institution hosted lectures by the era’s leading scientific minds, drawing crowds so dense that navigating the street became nearly impossible. Meanwhile, members of the royal family were frequent visitors to Garrard and understandably reluctant to be stuck in the crush. To ease the flow of both pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages, authorities converted Albemarle Street into a one-way thoroughfare—a rare blend of urban planning inspired by science, society, and royalty.

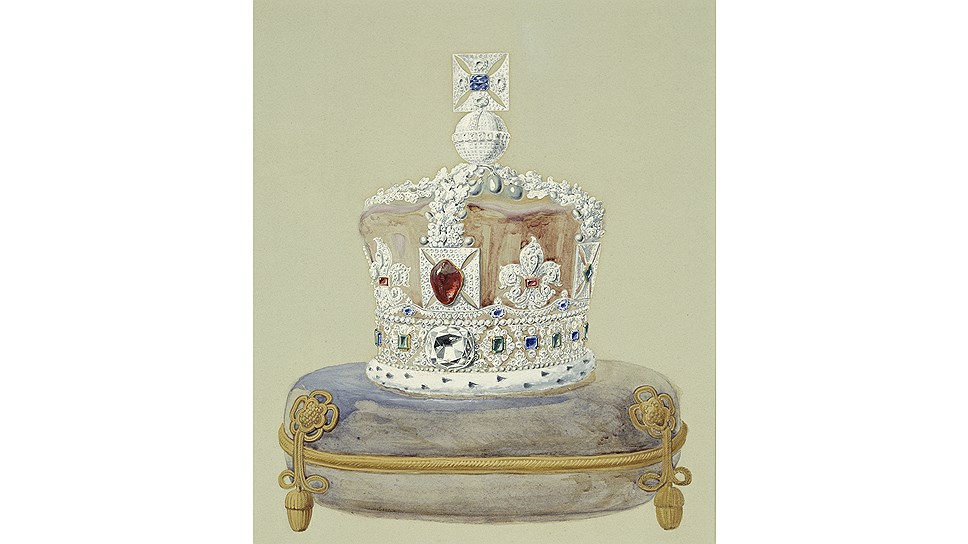

The Crowns of the British Empire

“We have crafted just five crowns for British monarchs,” begins Jessica Cadeau, Garrard’s Director of Heritage, with the cheeky smile as we both ascend the grand staircase to the second floor. “This is the room of Queen Mary of Teck, grandmother of Elizabeth II. In 1911, upon becoming queen through marriage, she tried on her future crown right here.

We also created a crown for her husband, George V; for their son, George VI, who ascended the throne following his brother’s abdication to marry the American Wallis Simpson; and for the Queen Mother. The fifth crown in the collection is a mourning crown, made for Queen Victoria. When Prince Albert died, she refused to wear a celebratory crown, and Garrard, by then the Crown Jeweller, fashioned a miniature crown, visible in her later portraits.”

Interestingly, the office of Crown Jeweller was created by an act of Parliament specifically for Garrard—a position born out of a royal misunderstanding. During her coronation, Queen Victoria wore a necklace and earrings she believed to be part of the Crown’s holdings. In fact, they belonged to her grandmother, Queen Charlotte, who had bequeathed them to one of her fifteen children.

In 1839, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, a royal relative, sued Victoria, claiming that a significant portion of Victoria’s jewellery, including the disputed necklace and earrings, was legally his. After extensive archival research, the court ruled in his favour in 1857.

While the case was ongoing, a frustrated Victoria ordered a meticulous inventory of her jewels—and instructed that the necklace and earrings be replicated. Garrard, with its unparalleled expertise not only in gemstones but also in licences and jewellery law, was uniquely equipped to carry out the task.

“The company was founded by George Wickes in 1735. At the time, his services were sought by Frederick, Prince of Wales,” explains Jessica Cadeau, opening a massive antique folio preserved behind glass. “In 1792, the firm was acquired by Robert Garrard, who brought his sons into the business. Under their stewardship, Garrard distinguished itself not only through exceptional craftsmanship—the all were talented jewellers—but also through sound management: stable pricing, fair-interest credit, and resilience in the face of economic crises.”

The company quickly earned a stellar reputation among Britain’s aristocracy. It is little wonder that Queen Victoria selected Garrard to inventory the royal jewels and replicate the necklace and earrings tied to such significant personal memories. In 1843, Garrard was appointed Crown Jeweller, and those very pieces remain in use by Elizabeth II to this day.

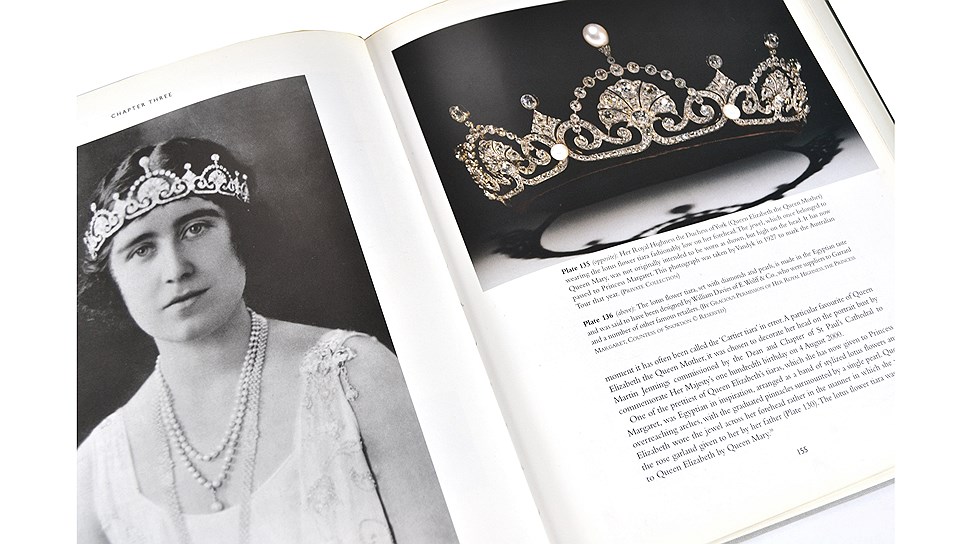

Beyond those earrings, Queen Elizabeth II wears a kokoshnik-style tiara crafted by Garrard, as well as her wedding tiara, also from the firm. Legend has it that on her wedding day the tiara was tried on so many times that it broke. The Queen Mother offered Elizabeth a replacement from Garrard’s extensive collection, but the young queen insisted on the original piece. Garrard’s jewellers, working just a floor above the boutique on Albemarle Street, rushed to repair it in time.

This is far from the only Garrard creation to play a starring role in a royal wedding. The iconic sapphire engagement ring inherited by Kate Middleton from Princess Diana was also crafted on Albemarle Street, reinforcing the house’s enduring connection to Britain’s monarchy.

Garrard’s craftsmanship earned admiration far beyond the British court. On page 84 of the firm’s order book is a list of jewels commissioned by Emperor Alexander II of Russia, including a diamond- and pearl-encrusted brooch costing £3,500—roughly £2.8 million today. The emperor paid in cash during visits to London to see his daughter, Maria Alexandrovna, who was married to Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s son.

“They say that when Maria Alexandrovna appeared at Queen Victoria’s court, she immediately won her over,” explains Jessica Cadeau. “But it wasn’t just her character or manners. Maria was a billionaire who dressed impeccably—able, in some ways, to outshine the queen herself. And her father ruled an entire empire, not merely a kingdom. Yet Victoria would not be outdone; she went on to build her own empire.”

Thanks to Victoria’s influence, Garrard soon began creating jewels and regalia for the elite across India and Asia, cementing its reputation as a jeweller of global renown.

Garrard retained its status as royal jeweller until 2007. “Then came a new era,” Jessica Cadeau smiles. “The royal accounts became fully transparent, and the role of official jeweller was put out to tender. Today, it’s simply a contract for a number of years. Still, we were delighted to secure last year a three-year agreement to create the trophies for the Royal Ascot. We have made almost all of these trophies historically, so in the new landscape it is important for us to know that for the next three years, this privilege remains ours.”

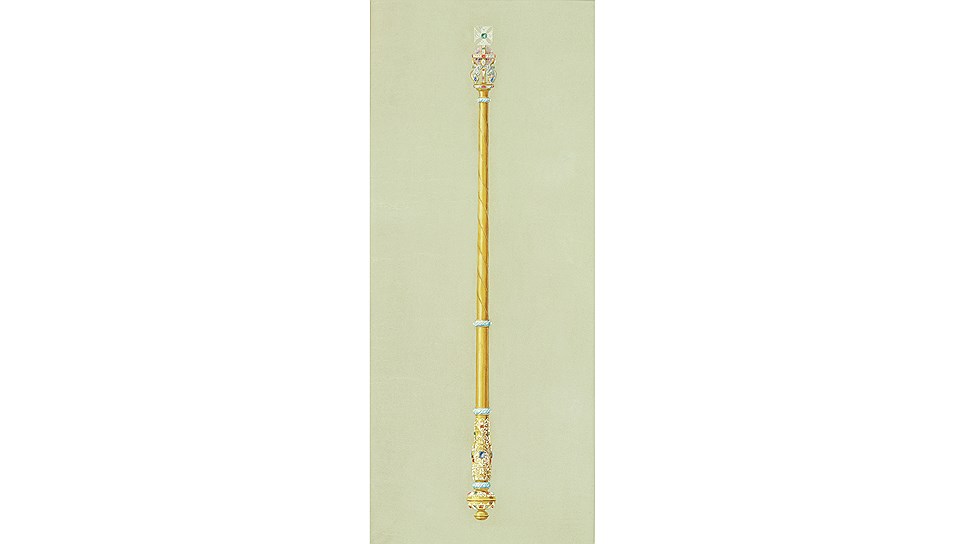

Trophies and silverware form the second pillar of Garrard’s enduring legacy. In any serious silver collection, one can expect to find Garrard cups, platters, forks, and knives. Sporting trophies sit naturally alongside tableware.

Awards for sporting events in the shape of cups began to appear in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. People were mindful of money even then, and if you were to gift someone a silver ingot, it had to be practical. A cup, after all, can be used for drinking—perfect for toasting a victory. Horse racing has long been a quintessentially British sport, and at the Royal Ascot, the award is presented by the monarch herself. So it was only natural that, as royal jewellers and silver specialists, Garrard eventually began crafting cups for Ascot and other prestigious sporting events.

The most famous of Garrard’s sporting commissions is undoubtedly the 1851 America’s Cup—a massive silver ewer that has long served as the challenge trophy awarded to the fastest yacht in this prestigious regatta.

“We also create contemporary trophies,” Jessica Cadeau explains. “For the Derby, we crafted a silver horse sculpture encased in an acrylic block. But Ascot is different. It’s a traditional event attended by up to 80,000 people, and the design of the cups must be approved each year by the royal commission and the Queen herself. That’s why we selected five traditional forms and offered several variations in handles and lids. Each cup is just over 30 centimetres tall, with a 10-centimetre pedestal. We don’t even need to create new casting molds—they exist in our archives. Yet each trophy still takes up to 12 weeks to make, because at Garrard, this is not merely design—it’s three centuries of expertise.

In addition to the five gilded cups, we produced 90 silver rulers engraved with the names of all Ascot-winning horses, and we plan to make 90 smaller silver cups for toasting the horses on which punters placed their bets. All of this is in celebration of the Queen’s 90th birthday on 11 June.

“I particularly love the choice for the main Golden Cup, awarded to the winner of winners. To claim it, a horse must be not only strong and resilient but truly impressive. Its design should reflect power, stability, and awe. Although the cup’s shape traditionally changes each year, I asked the commission if we could keep last year’s golden cup unchanged, as its form is perfect. They said they would ask—and they agreed. That’s my personal delight!”

Originally Published at Kommersant: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3007869

Leave a comment