By Kristina Moskalenko

Photography by Wanda Martin

The acclaimed documentary about Sergei Polunin – ballet’s most controversial prodigy – made its global debut at the BFI London Film Festival on October 8, 2016.

Once the youngest-ever principal dancer of the Royal Ballet, Sergei Polunin shocked the world when he walked away from the company, sporting a fresh set of tattoos and a rebellious attitude. Since then, he’s graced Russian TV screens in sequin-studded prime-time shows, danced hauntingly in David LaChapelle’s sun-drenched video for Hozier’s Take Me to Church, and even fronted campaigns for Diesel jeans.

Ballet and Diesel — who could have imagined the two sharing a stage? And how did a boy from Ukraine become the enfant terrible of British ballet?

That’s precisely the story British filmmaker Steven Cantor tells in Dancer, a raw and riveting portrait of Polunin’s meteoric rise and dramatic fall.

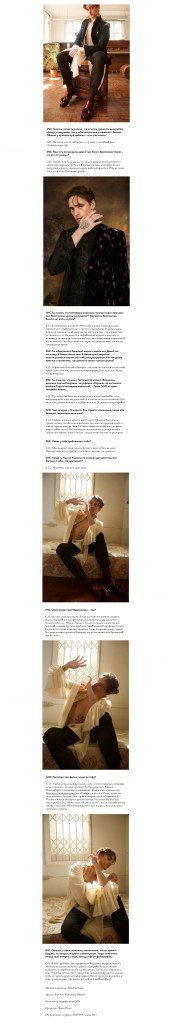

With press buzzing around the film, Sergei is in high demand — but we manage to steal a moment with him in London, backstage at an SNC photoshoot. Surrounded by brushes, lights, and stylists, he tucks our voice recorder into the breast pocket of his striped sailor tee — close to the heart.

SNC: Sergei, people say you’re difficult to reach. You disappear, don’t answer calls or messages. And now, just before Dancer premieres, suddenly you’re accessible – thanks to your new, very strict British agent.

Sergei Polunin: I threw my phone away for half a year. I had to disconnect from everything – the noise, the system – and go back to myself. Since childhood, the world tries to program us: school, society, even family. And slowly we forget who we really are. But children — when they say they want to be astronauts or artists — that’s real. That’s truth before it’s edited. I wanted to return to that. As a kid, I loved nature. Not in a casual way — I felt connected to trees, animals, people… everything. It was a kind of pure love. I needed to go back to that space. To remember.

SNC: And when you still had a phone — what icon or emoji did you use most?

Polunin: I didn’t use any of that. I had an old Nokia until just last year. Never owned an iPhone. All of that — it’s distraction. We’re surrounded by things designed to pull us away from who we are. Advertising, television, phones… it’s constant manipulation. People live in a digital fog. But the real journey is inside. So I got rid of the tools that were pulling me outward.

SNC: That’s a strong choice — most people would never give up their phone. It feels impossible today.

Polunin: It was incredible. For me, at least. Maybe not for everyone else. (Laughs.) But imagine waking up and not feeling like you owe someone a reply, or like you’ve already fallen behind. There’s a freedom in that. No pressure. Just silence. Space.

SNC: Do you like people? Who do you enjoy being around?

Polunin: I don’t really think in terms of like or dislike. I feel energy. I can sense it very quickly. I’ve learned not to judge people — that’s something acting taught me. If you judge someone, you can’t understand them. And as an actor, you need to understand every character, even the darkest ones. That taught me to be open. To everyone.

SNC: What qualities attract you?

Polunin: In women, it’s softness — something sacred. In men, it’s strength. Not physical strength — real, inner power. That quiet kind.

SNC: And what disturbs you? Surely the “bad boy of ballet” gets angry sometimes?

Polunin: (Pauses.) Disrespect. When someone is rude or talks down to others — that energy feels wrong. But honestly, the people around me, the people I work with — they’ve become like family. I trust them deeply. I treat them like I would treat my own blood.

SNC: Is there one strong emotion that drives you?

Polunin: The desire to keep moving forward. Not to stop. Not to go back. Only forward. The most important thing is simply to do. People will judge later whether it was good or bad — that’s not my job. My job is to keep going. A lot of people I know spend too long analysing, planning. I believe you just need to move. Once you start, the right people and ideas come to you. Movement creates momentum.

SNC: That’s interesting, because you talk about action rather than thought — but from the way you speak, I’d say you seem like an introvert.

Polunin: I am. Deeply. I’m just in a phase of action right now. But before this, I needed full isolation to understand what I truly wanted. Now I’m clearer on my direction, so it’s time to act. But yes — I come from silence.

SNC: You’ve become known for walking away — from performances, from theatres. How do you know when it’s time to leave?

Polunin: I wouldn’t say “walk away.” It didn’t happen as often as people think. But because of how dramatic the Royal Ballet story was, it became a label. I was 19 — the youngest principal in their history — and three years later I left and went to Moscow. People turned it into a scandal, especially when I admitted to using cocaine before going on stage. But for me, it was instinct. A deep knowing. I’ve had very few moments like that in life — but when I do, I trust them. Of course, I have a brain, but I actually advise people to turn theirs off sometimes and just feel. Intuition is like water, like wind — you don’t control it, you follow it. Every time I tried to control life, it led me somewhere dark. But when I just moved — without thinking too much — good things happened.

SNC: So your “bad boy” image — it’s not a PR strategy?

Polunin: Not really. It’s just how people interpret me. They see something negative, when actually I’ve always moved toward what felt right. Sometimes it broke me. Sometimes I even believed what the press wrote. And yes, sometimes I played into the scandal, let that image speak. But I always tried to listen to myself above all.

SNC: Where do you see yourself now?

Polunin: I want to act. But I don’t make big plans. I trust life. If you surrender to it, it brings the right roles.

SNC: Is there a dream role? Black Swan? Rambo?

Polunin: I love those, but I’ve already been Rambo.

SNC: Let’s talk about Take Me to Church. That video didn’t just make you world-famous — it almost seems like it broke you.

Polunin: David LaChapelle — the legendary American fashion photographer — reached out with the idea. He’d heard Hozier’s track and suggested I dance to it. I listened without diving into the lyrics, just felt it. And instinctively, I understood it. That piece marked a turning point. At the time, I was ready to quit dance altogether and go to film school to become an actor. But this… this reminded me that dance could still do something good — that it still had meaning for me.

SNC: Your tattoos are just as famous as your dancing. Which one has the most interesting story?

Polunin: Maybe the tiger paw. I originally wanted to get it done as scarification, but it was Ukrainian Independence Day in Kyiv, and the studio wasn’t really functioning. So I ended up with a tattoo — too orange, too bright. I had to scrape the color out of my skin later. I think it was my first one. I never think too long about a tattoo. I just wake up and go with what’s in my head. I liked being in tattoo studios — the people, the vibe. And the adrenaline from the needle. It puts you in a good mood for days afterward. I haven’t gotten anything new in about a year, but if the moment feels right again, I will.

SNC: I know you’re close with a lot of tattoo artists and even invested in the business at one point. How did they take to a ballet boy walking in?

Polunin: They were cool. You can find common ground with anyone. There are no bad people — just situations life throws at them. The energy you give out is the energy you get back. If you don’t judge someone, they won’t judge you either.

SNC: You said you had to scrape the color out — that’s an intense relationship with pain. Most men start moaning if they get a toothache.

Polunin: I actually hate pain. I’m super sensitive to it — especially toothaches.

SNC: Okay, tattoos done. Let’s talk ballet. What’s the British ballet scene like?

Polunin: Honestly? I’ve never been that interested in ballet as a scene. I don’t love talking about ballet. The atmosphere’s good, but I’ve always felt more connected to the outside world. I wasn’t close with many people in the ballet world.

SNC: That’s interesting because in movies about ballet it always seems like a battlefield. Was it really not cutthroat?

Polunin: No, it is cutthroat. You’ve got 90 dancers competing for one spotlight. That’s just the structure. And the problem is systemic. In opera or film, you sign a contract — it’s clear who plays what, what’s expected. But in ballet, roles can be given or taken away in a second. That creates toxic energy. I’d change the whole setup if I could. It would benefit both the dancers and the companies. Give artists more freedom — more time to grow.

SNC: You joined the British ballet school when you were just nine. Let’s be honest — ballet has long had strong representation from the LGBTQ+ community. That’s also true in many all-male boarding environments in Britain. How did it feel for someone who identifies as traditionally heterosexual to grow up in that world?

Polunin: It was fine. I never saw barriers — not in terms of sexuality, not in terms of race, not in anything, really. Who sleeps with whom? I’ve never been interested in that. It’s not what defines a person.

SNC: You once said that you and Natalia Osipova — your partner and fellow dancer — weren’t allowed to perform together. Is that true?

Polunin: There was definitely a sense from the leadership of “divide and conquer.” It’s easier to control people when they’re separated. But I believe the opposite — unity brings strength. If people come together, they can fly to Mars. But that understanding takes time.

SNC: What’s it like being in a relationship where both partners are powerful creative forces?

Polunin: It’s challenging, especially at first. We were constantly traveling, never home at the same time, and certainly not thinking about who’s cooking dinner. But it’s nothing impossible. People can adapt to anything. If you’re hungry, you order in. You find your rhythm.

SNC: What’s the one thing you demand of yourself?

Polunin: Not to break. There’s a lot in this world that can pull you down, crush your drive. So I always tell myself: stay strong. Don’t let it break you.

SNC: When you were filming your documentary back in Ukraine, what did you feel?

Polunin: The energy there — it’s powerful. It gives you strength.

SNC: There’s that word again — energy. Is Ukraine still your homeland?

Polunin: Honestly, I don’t even know what “homeland” means anymore. The word feels a bit absurd to me now. Once you spend time abroad, you start to see the world as something much bigger than “you’re from the South, I’m from the West.” I saw a news story recently about a double amputee soldier who ran the longest desert marathon on prosthetics. The headline said, “A national hero Britain can be proud of.” But why only Britain? Shouldn’t all people be proud of him? Saying he’s just a British hero — that’s too small a frame.

SNC: Tell me about your documentary. Why did you want to make it?

Polunin: It didn’t start with the idea of telling my story. I wanted to open up a little — to film everywhere, to show that every place has its own kind of beauty. That was the point. I remember living in Novosibirsk and still being stunned by the nature there — the snow, the stillness. Everyone in London imagines Siberia as this barren, empty place. Even after nine years in London, I was scared to travel to Ukraine and Russia again. I was afraid of reentering another culture. I didn’t know how to speak anymore, didn’t know what might offend someone or not, didn’t even know how to buy milk at the corner shop. But eventually, I realized — the world over, people are the same. Same worries. Same kids. Same life.

SNC: I get the sense that you’re something of a spiritual minimalist — almost Buddhist in your detachment from the moment. So how do you explain your interest in fashion, in gloss, in high-concept photography?

Polunin: I worked with fashion photographers as a way to develop my acting — to become more comfortable in front of the camera. It wasn’t about fashion at all, really. Those shoots were my first steps in learning how to inhabit different roles. Honestly, I dream of owning a wardrobe made entirely of the same outfit — so I don’t have to waste time choosing what to wear in the morning. Maybe that will change one day. But for now, please don’t ask who my favorite designer is.

Photography: Wanda Martin

Makeup & Hair: Yulia Yurchenko

Model: Britt Fox / Wilhelmina Models

Photography Assistant: Santo Milo

Producer: Irina Pilat

Published in SNC Magazine, Issue No. 98 – June 2017

Leave a comment