By Kristina Moskalenko

This year, the Croisette isn’t just glistening with diamonds—it’s patrolled by soldiers in full combat gear.

They’re everywhere: composed, well-built, and striking enough to resemble cavalry officers from a period drama. As you pass, you might smile—perhaps even attempt a playful glance—but they remain impassive, fingers firmly resting on the trigger. Security, one must admit, is operating with military precision.

Leopard print is having a major moment.

The number of women in animal patterns is almost comic in scale—some enhanced with unmistakable cosmetic bravado, others simply beautiful. These feline figures flit from official parties to impromptu yacht gatherings with enviable ease. One can only speculate how some received their invitations—but this is Cannes, and the improbable often passes for standard.

Bras, it seems, have been left off the packing list.

There’s a noticeable absence of support beneath the season’s featherweight dresses. After London’s restrained silhouettes, it’s undeniably bold—and refreshing.

Robin Wright appeared on the red carpet in a vivid green backless gown that made an impression.

Above all, it was a moment of quiet revelation: her décolletage drew attention, accentuated with the sort of breezy elegance unique to the Côte d’Azur. Just hours prior, she had taken the stage at Kering’s Women in Motion event, offering frank reflections on her move behind the camera. With a wry smile, she quipped that Donald Trump seemed to be lifting plot points from House of Cards.

Wright also recalled an early casting experience, where she was asked to reveal her chest. She obliged—only to be told: “The previous girl’s breasts were better.” In Cannes this year, the theme of female presentation—liberated or otherwise—has been explored in full.

Wright spoke about championing women in film and equal education from the earliest years. Behind her, yachts drifted across the Mediterranean, gulls circled in the sky, and the sea shimmered like liquid silver.

Outside, the promenade told its own story.

Among the glamorous crowds wandered a notable number of fathers with prams and small children, many in business-casual attire—perhaps fitting in parenting between panels. Meanwhile, older women—hat-clad and tastefully translucent in chiffon blouses—lingered over ice cream, while their male counterparts reclined on benches, taking in the procession of leopard print with quiet appreciation. An unofficial festival, if you will.

A diplomatic footnote: the Indian and Dutch pavilions share a space.

The Indian side of the pavillion is vibrant and welcoming—there is food, and plenty of it. The Dutch, by contrast, is quieter and somewhat austere. A robust Dutch hostess—disciplined and broad-shouldered—guards the imaginary “border” with near-military efficiency, ensuring no crossover occurs. The Indians joke that their colourfulness bars them from the paler, quieter corner—though blonde women, particularly those in plunging necklines, seem to gain entry everywhere without resistance.

At the Magnum party, Cara Delevingne was present, but elusive.

She remained within the velvet-roped VIP section: bald, striking, and dressed in a dark, moody palette with matching black lips. She neither danced nor drank, and made no move toward the ice cream. Possibly the reason she remains so elegantly waifish. But glitter rained down nonetheless, settling gently over her, as it did on the dancers and the dessert-lovers alike.

Because in Cannes, even those who remain still are part of the spectacle. But not everyone has stayed still or frozen. A squadron of muscled men in stilettos and satin lingerie, gleaming under massage oil looked on stage like they’d walked straight off a Kazaky music video. Think burlesque meets boot camp. Finally men in heels are entertaining moody women and not vice versa.

When it comes to Cannes connections, charm trumps credentials.

Start a conversation with something frivolous, smile, and voilà — you’re swapping numbers or sipping espresso before you can say “distribution rights.” This, for instance, is how I found myself in discussion with the former head of the French Film Commission. It all began with a smile, returned. As it should be.

Later that day, over mineral water (he’s a purist), he explained how he negotiates filming permits for Hollywood crews in Paris’s most elusive corners. When the temperature dipped, he placed his jacket over my shoulders without a word. “But if I put something on,” he added, lifting my sunglasses from my face, “I must take something off.” He looked into my eyes. Honestly? The French still have it.

Who knew a war film presentation could feel like stand-up?

At the unveiling of T-34 Russian war drama, producers Ruben Dishdishyan and Leonard Blavatnik bantered breezily with journalists about the film’s 600-million budget. No one batted an eye. But then came Hollywood’s Brett Ratner (Rush Hour, X-Men: The Last Stand), who did a double take. Eyes wide, he seized the microphone: “Wait—600 million?! 600?! Wonder Woman got 200 million, and that’s a blockbuster! You’re calling T-34 low-budget?” Cue the laughter. Someone leaned in to explain: rubles, not dollars. The room erupted and for a moment, war cinema had never felt so light-hearted.

On the Russia Pavilion’s veranda, rising actress Maria Darkina was a picture of poise.

She stars alongside Monica Bellucci in Emir Kusturica’s On the Milky Road.

“What was it like working with Monica?” I asked.

“The first time I was meant to meet her, the wheel fell off my car. Serbian backroads, middle of the night — two hours waiting for the police. The meeting was cancelled. But we eventually met at festivals. She’s incredibly modest. A true lady. When she came to Moscow, the men — how do I put this? — they melted. My mother said, ‘They bloomed like a broom on a rubbish heap.’”

Bellucci learned Serbian for the role, and how to milk cows. Naturally.

“And how was it to work Kusturica himself?”

“Terrifying. He says very little, looks severe. You never know what he’s thinking. You have to feel it, improvise. Many actors panicked. I… adapted.”

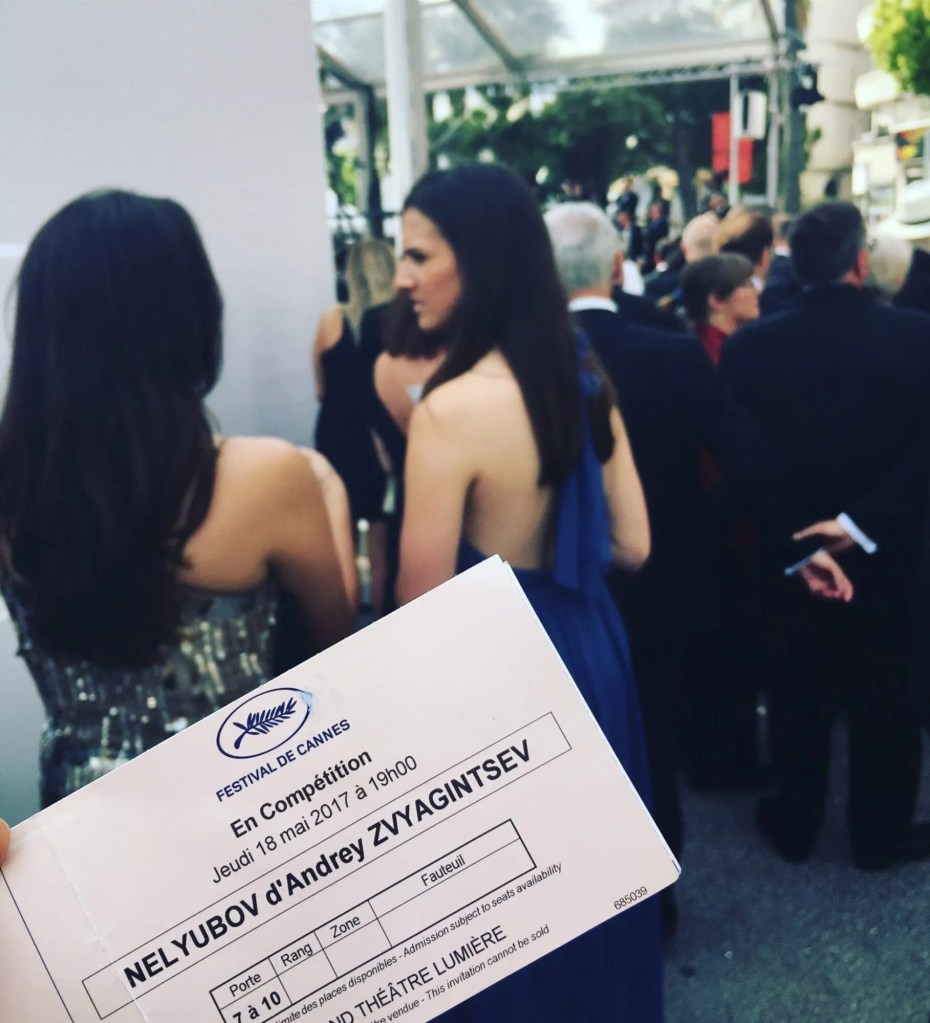

Finally, by that evening the team behind Zvyagintsev’s Loveless took to the red carpet with such solemn grandeur, it looked less like a film premiere and more like a cosmonaut send-off.

Think Belka and Strelka, but in tuxedos.

Foreign critics are raving about Loveless. If you missed it: in the opening scene, Maryana Spivak curses awkwardly and emotes through clenched teeth. But by the end, she hits her stride — either she improved, or your eye simply adjusts. Not to the tears, but to the performance. Andris Keišs’s role? A walking fantasy — the man who hugs, chauffeurs, dabs away tears and always says “yes.” Slightly too convenient, perhaps.

Just outside the Palais des Festivals, where all the magic supposedly happens, the scene is surreal.

Tiny Chinese girls in designer shorts stand shoulder to shoulder with burly men in Breton stripes, all clutching cardboard signs scrawled with: “Ticket wanted, s’il vous plaît.” That polite little s’il vous plaît somehow melts the heart.

A few steps away, in the middle of the traffic lane, stand women of quiet dignity—elegant, silver-haired, dressed in pale linen, sandals, and soft-brimmed hats. Also hoping, gently, for a red carpet ticket. Any will do. You long to slip them yours—but alas, press credentials don’t come with red carpet perks.

Producers, however, are another story. They get tickets. To become one, you need only shoot a film—no matter how obscure (singing bowls, orphaned children, take your pick)—and pay a membership fee to some association of emerging creatives. Or skip the formalities entirely: acquire a producer friend. One who, charmed by a Mona Lisa smile bestowed just for him, might conjure a precious ticket out of thin air.

Rule one of the red carpet: confidence trumps credentials.

Cameramen often have no clue who’s who. Show up shimmering, tighten your silhouette, strike a pose à la Jolie, toss your mane, and smile as if the promenade bears your name — and just like that, you might pass for a beloved icon from some far-off province.

For the paparazzi, it means taking a hundred shots — just in case the local paper, The Sun, later decides to pay a tidy sum for a photo of its homegrown celebrity. The ladies make the most of this. But it takes practice.

But don’t underestimate the theatrics.

The photographers don’t so much call for your attention as howl, as if summoning a rare Pokémon or preparing to burn a witch. “This way!” “Over here!” “Look left!” — a chorus of frenzy. The trick is to pose like a pro until a stony-eyed official instructs you to move along.

Unless you’re Scarlett Johansson, you’ll be herded along the carpet like glamorous livestock.

Socialites teeter in heels, wrestle with dresses, and fumble for their front-facing cameras — but always make it fashion. The result? A few flattering frames on Getty Images. But the film itself? Entirely optional. Sit by the aisle, ditch the heels, hitch up your dress and slip out after five minutes for cocktails with the girls.

By 9 p.m., the cafés near the Palais are shimmering with mermaid-haired girls in gowns that defy gravity.

I overhear Russian guests, who were not impressed when model Winnie Harlow sashayed down the red carpet proudly baring her vitiligo. “But what does it mean?” they asked, clutching pearls. But honestly — why not? She might as well have painted herself green. It’s Cannes. Harlow, for her part, seems to draw missing patches for symmetry.

As for Irina Shayk, everyone is desperate to know what she looks like post-baby. The answer? Exactly like Irina Shayk. Glorious.

The true professionals, meanwhile, remain immune to the glitz.

They roam Cannes in sensible shoes and rumpled linen, as if dressed by their grandfather’s valet. They remember the festival before the red carpet became a runway. And they sigh.

One such veteran — producer of Gangs of New York, The Rum Diary, The Young Victoria and My Week with Marilyn — was once denied entry to a party for not meeting the dress code. His offence? An insufficiently formal jacket. Now he refuses to attend anything unless he’s invited three times, in writing, by name. You’ll find him these days on the lawn of the Le Grand Hotel, sipping whisky and smoking cigars, far from the madness. And frankly, who can blame him?

Of course, not everyone carries their credentials like crowns. There exists a whole breed of seasoned professionals—mildly famous, fully ambitious—who’ve elevated gatecrashing to an Olympic sport. Why wait for an invitation when you can charm the clipboard-clutching Cerberus at the door, slip under the velvet rope, shadow Gigi Hadid’s handbag, or snatch a glimpse of the guest list from an overworked assistant’s trembling hands? Throw in a touch of method acting, the reflexes of a panther, and the night is yours.

And what nights they are.

The introductions themselves are stories. One moment, you’re standing on a street corner in a hemline that’s only socially acceptable in Cannes after sundown; the next, a dashing gentleman in an unbuttoned shirt with ruffles appears like a mirage, his gaze ablaze with post-party ambition. He doesn’t bother with pleasantries—he’s fresh from a soirée where the ratio of legs to lingerie was simply unsatisfactory. With the enthusiasm of a teenager and the finesse of a seasoned rake, he sweeps you off your feet.

Later, you discover he’s Antoine Verglas—the very man who, in 2000, photographed a naked Melania (then Knauss) draped in diamonds and furs for GQ. These days, he still shoots beautiful women for glossy covers, their clothing optional.

“Melania? Incredibly clever woman,” he murmurs, over the second rosé. “They’ve tried everything to dig up scandals, but still—nothing. Her only flaw? That charming accent, which the French adore. She never wanted the spotlight. She has spectacular legs.”

The following morning, you reconvene to discuss the philosophy of nude photography. Instead, he grabs a poster for François Ozon’s L’Amant Double and turns it into an impromptu erotic thriller. A true artist’s eye, you see.

Back to the parties.

Even with a golden ticket, entering some of these soirées feels like navigating a couture stampede. Which is why the rooftop wine bar Mouton Cadet atop the Palais des Festivals is a true oasis.

Designed by rising French interiors star Mathias Kiss (Google his take on perspective—ideal inspiration for your powder room refresh), the terrace hosts everything from midday press interviews to parties. It’s also where Pedro Almodóvar, Jessica Chastain, Paolo Sorrentino, and the rest of the jury gathered pre-closing ceremony—officially making it a sacred space. Eva Longoria hosted her Global Gift gala here, and Swedish Palme d’Or winner Ruben Östlund gave interviews between chilled glasses of rosé. It’s Cannes with a view—and a pulse.

A pink-themed Ice Party at the Mouton Cadet rooftop was a hit, and the dress code inspired both flair and fun. One guest arrived in a flamingo-covered suit — none other than designer William Arlotti. His dreamy, diaphanous gowns in every imaginable blush hue shimmered like confections, impossible to resist.

You find yourself wanting to slim down just to wear one — and then immediately reminding yourself you don’t have to. Down here, curves are adored. This is the South of France, after all: where a glass of icy rosé on a sun-drenched terrace is practically a ritual. Let a drop fall, lazily, onto your chest and catch the sunlight as it trickles down. Follow it with a bite of something decadent — a rose-hued strawberry macaron or a pale pistachio one — and let your hair tumble loose.

First stop before any of that?

A visit to the L’Raphael spa at the Hôtel Martinez is practically a Cannes tradition. It’s the go-to spot to recover from last night’s champagne — or to prepare for the next round. William Arlotti, master of the see-through gown, is a regular here, often turning the place into his personal runway.

Speaking of sheer genius — transparent dresses are everywhere. At the 70th Cannes Film Festival, it felt like everyone was floating down the red carpet in something barely-there and utterly fabulous. But the undisputed queen of the look? Bella Hadid. Her dress didn’t just make headlines — it rewrote them. If the old saying goes, “The emperor has no clothes,” Bella’s version would be: “The queen wears whatever she pleases.”

Meanwhile, designer Isabell Kristensen staged a fashion show inside the glitzy Casino club. Logic (and genre) suggested lingerie, but the models emerged in gowns—some exquisite, others resembling candy wrappers. Candy-coloured couture was everywhere this year, from Eva Longoria to Kendall Jenner. And in Cannes, even a sweet wrapper can be high fashion—if worn with the right smile.

Marion Cotillard looks like a porcelain doll.

I ran into her in the Marriott elevator. No autograph—just stood there mesmerized.

Michel Hazanavicius confessed that the writer of the book that his latest film is based on initially refused to sell him the rights. But then he wrote her a letter saying he found the book funny. “You must be from another planet,” she replied. “No one but me thinks it’s funny. Let’s meet.”

Moral of the story? When you’re denied something—say you find it amusing. You might just get a yes.

When Hazanavicius asked Louis Garrel to play Godard, Garrel replied: “So… you want me to play Jesus?”

Hazanavicius said, “I don’t expect a driving instructor to play a Formula One racer, but yes.” Which, of course, was a compliment.

Though the 70th Cannes Film Festival was widely declared a feminist one—with much talk of celebrating women’s achievements in cinema and beyond—the actresses at the pressers mostly sat wide-eyed, waiting for their male co-stars to finish monologuing before being allowed a polite 30-second interjection.

Feminism, it seems, is still on pause—until granted permission.

At a party thrown by an Indian magnate at his villa, the ladies’ room was a marble-draped paradise of flowers and mirrors—but lacked one crucial item: a bin.

Gentlemen, if you’re inviting a flock of women to your lavish estate, please install a wastebasket. With a lid. It says more about you than your orchids do.

Of course, Cannes has everything. Including minor European royalty.

At the Peace Rally cocktail reception, one could mingle with Countess Geneviève de la Pommelière-Lafayette, Princess Olga Romanova, Countess Elisabeth von Alexander-Bismarck, Prince Guido Arangio degli Estensi, Knight of the Order of Malta Francesco Russo, San Marino’s Special Envoy Mike Bruschi, and UN rep Jean Bernard.

These nobles drove their vintage automobiles from Monaco to St. Petersburg in impeccable form. Prince Serge Vladimir Karađorđević of Yugoslavia set off in a 1953 Rolls Royce Silver Wraith, while Prince Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy, Prince of Venice and Piedmont, chose a 1960 Bentley S2.

Guests murmured, “What if one of these cars doesn’t make it?” But everyone posed with them anyway—because who wouldn’t want a photo with a vintage Bentley? Every car made it, and the rally may now become an annual affair.

At Nikki Beach, the Elysium Bandini studios hosted a fête for Joaquin Phoenix’s psychological thriller You Were Never Really Here.

Thirteen-year-old Russian-Ukrainian actress Ekaterina Samsonov, now based in LA (where else for a girl with such a genetic cocktail?), plays a trafficked girl in the film. Dressed in Chanel, she looked like a living porcelain figurine.

Guests sipped Perrier-Jouët and learned about a streaming platform offering films, documentaries, and interviews for $10 a month—all in support of young artists bringing art to hospitals, prisons, shelters, senior homes, and schools for troubled children.

Saving the world—Cannes-style—one flute of champagne at a time.

Joaquin arrived with his sisters Summer and Rain—yes, really. Guess what the weather was when they were born? He also wore proper dress shoes, which made headlines simply because he’d accepted his Best Actor prize at the closing ceremony in sneakers.

Speaking of the closing ceremony: it was flawless.

Monica Bellucci held the most demanding role of the evening—standing and radiating splendour. Sounds easy? Try doing it for two hours in couture. She also delivered a 30-second speech before returning to her prime duty—looking divine. But Monica wouldn’t be Monica if she hadn’t subtly signalled her sovereignty via a coquettish butterfly pattern placed precisely where a fig leaf might go.

Just so we all knew who was boss.

And yes, it was the most elegant undressing of the festival.

Though many tried. The amfAR Gala—ostensibly a benefit for AIDS research—is, for some, simply a competition in creative disrobing. Bella Hadid led the charge.

Yet to truly master the art of provocative dressing down, one must turn to Emily Ratajkowski. It’s not just about revealing—it’s about revealing with panache. Honestly, she should teach classes.

When it comes to fashion, the best-dressed crown undoubtedly goes to Kendall Jenner in Ralph & Russo at the Chopard soirée.

And then there’s Leonardo DiCaprio, who managed to orchestrate the perfect breakup just before the festival. He rented a villa, invited 150 models, and seemingly vanished into the background.

Was he hosting, or perhaps quietly inspecting? After all, he was definitely not watching those guests who were scaling fences or tunneling their way in.

It was the kind of party where the host is a mystery, and the spectacle was entirely of his own making.

The whispers of Cannes had one prediction: Andrey Zvyagintsev would take home the prize.

By 2 pm on awards day, the phone rang to confirm he was in town—though nobody was quite sure where the call had come from.

But then again, rumors are like a fragrance. The subject and body may be absent, yet the presence lingers.

The air at the closing ceremony crackled with anticipation for Zvyagintsev.

My phone was down to 10% battery, but I had every intention of saving it for that moment when he took to the stage with the Palme d’Or. His name came unexpectedly early, and I barely had time to switch on my camera. But it also meant that he was not the winner! And I had been sitting there, captivated by Monica Bellucci—unfazed by the French chatter—waiting for the powerful Russian speech I expected at the end. He won the Jury Prize.

The minor heartbreak led me to join British director Kemal Akhtar for a drink.

He, too, was rooting for Zvyagintsev. We then made our way to the closing party, where we rubbed shoulders with Oscar winners and Palme d’Or honorees, sipped champagne, and indulged in the chocolate fountain.

Oscar-winning Barry Jenkins—the man who famously dethroned La La Land with Moonlight—gently embraced a procession of starstruck blondes, possibly scouting inspiration for his new series Dear White People.

By the time we left, it was nearing 4 am.

My heels had comfortably found a resting place in a pair of strong male hands. And then, there he was—Zvyagintsev, standing on the Croisette with women’s heels in hand, like a bouquet.

The men exchanged winks, their heels gently clinking together, before delving into a spirited conversation about cinema and the festival itself.

The heels, however, remained firmly in their grip, held close to the heart, as Zvyagintsev’s wife arrived from the nearby hotel, shifting uncomfortably from foot to foot, her bare soles feeling the warmth of the Cannes pavement.

As for The Square, which claimed the Palme d’Or, it is a tour de force of contemporary art and societal critique.

If Loveless is a masterclass of meticulous cinema—a symphony of perfectly calculated tension, Fibonacci’s golden ratio adhered to, and symbolism served on a silver platter—then Ruben Ostlund’s The Square is modern, irreverent, and daring.

While it won’t make its way into university syllabi anytime soon, those with an eye for art and media will certainly find their own lives reflected in its every frame.

Leave a comment