By Kristina Moskalenko

Career failures are not a typical topic of conversation. For Russian-British financier Stuart Lawson, however, they are a favourite. He has even created a masterclass, “Successful Failure.”

“My career as a banker spans 35 years, and I’ve made mistakes,” he says, pouring tea. “But I’ve come to realise that much could have been done faster and more efficiently, and some stages of my career were far harder than they needed to be. My goal now is to shorten the path to a successful career by teaching people how to handle failure effectively.”

We meet at his home in London. There is a view of the river, a sculpture of a greyhound by the entrance, and a magnolia in bloom. In the first room, a painting of a sailor immediately catches the eye.

“A gift from Ilya Lagutenko,” he explains. Noticing my puzzled look, he continues: “In 2004, I became head of Oleg Deripaska’s bank, Soyuz. We decided to cultivate clients from a young age and focused on students. Deripaska liked the band Mumiy Troll and suggested Ilya become a brand ambassador. In the end, we became friends.”

Lawson arrived in Moscow in 1995, when he was appointed executive director of Citi in Russia. Before that, he had spent 20 years as a crisis manager for banks in the UK, Greece, Egypt, Italy, Kenya, Norway, Puerto Rico, the US, and France.

“Russia, 1995 — the banking system was just taking shape. I got along well with the young local staff, but ran into problems with experienced expatriates who did not accept my management style, and fairly soon I was sent to Puerto Rico,” he recalls.

“During a layover at Heathrow, I met Dennis Martin, the corporate executive vice-president for emerging markets — essentially my boss’s boss. He said: ‘We put you in charge of the bank to be Caesar: to sit on the throne and give a thumbs-up or thumbs-down. But you acted like a gladiator, throwing yourself into battle by habit.’

“Before that comment, I had been convinced my management style was perfect, because until then I had never had any problems with it. From that moment, I realised how important it is to look at yourself not under the soft glow of candlelight, but under the harsh light of a fluorescent lamp. Recognising the part of the responsibility for a situation that lies with you is always a chance to learn something — and that is exactly what I did.”

Even in Puerto Rico, Lawson’s career did not follow the conventional path of promotions and successes.

“On 22 September 2000, I left Citi over disagreements with its lending policies,” he recalls. “I had always been certain that I was a ‘Citi banker’ and could be nothing else. But on 23 September, I woke up not knowing who I was. That was when I learned the second lesson: after a fall or failure comes a period of emotional turmoil. You have to allow yourself to experience it — drink, complain, sulk, get depressed, keep a diary, drive your family and friends crazy.

“But at the same time, it is important to focus on what you can control under the circumstances: exercise, hobbies, family. And crucially, this state cannot last more than a year. You can feel sorry for yourself, but not indefinitely; you shouldn’t let it drag on.”

Friends helped him climb out of the emotional pit. “They invited me to live with them in Manchester and take part in launching their website, littleblackdress.co.uk,” he says. “It was the most natural way to occupy myself with something positive.

“Therefore, the third important aspect of dealing with a career setback is having a wide network of friends from different professions. While working at Citi, I never lived anywhere for more than two years.”

When arriving in a new country, I spent a month visiting local bars and inviting regulars to parties. The condition was that they bring friends. In Milan, I was placed in a semicircular apartment. One evening, I went to the kitchen for another bottle of wine for my banker colleagues and saw a lively group through a window at the opposite end of the building. In my head I thought: “It’s a pity I’m not there.” Then I realised it was the other end of my own apartment.

“More broadly, the wider your circle of acquaintances, the better you absorb what life throws at you. For twenty years my career had gone in a straight line, despite being a crisis manager sent to places on the verge of collapse. But in a few years, everything changed.”

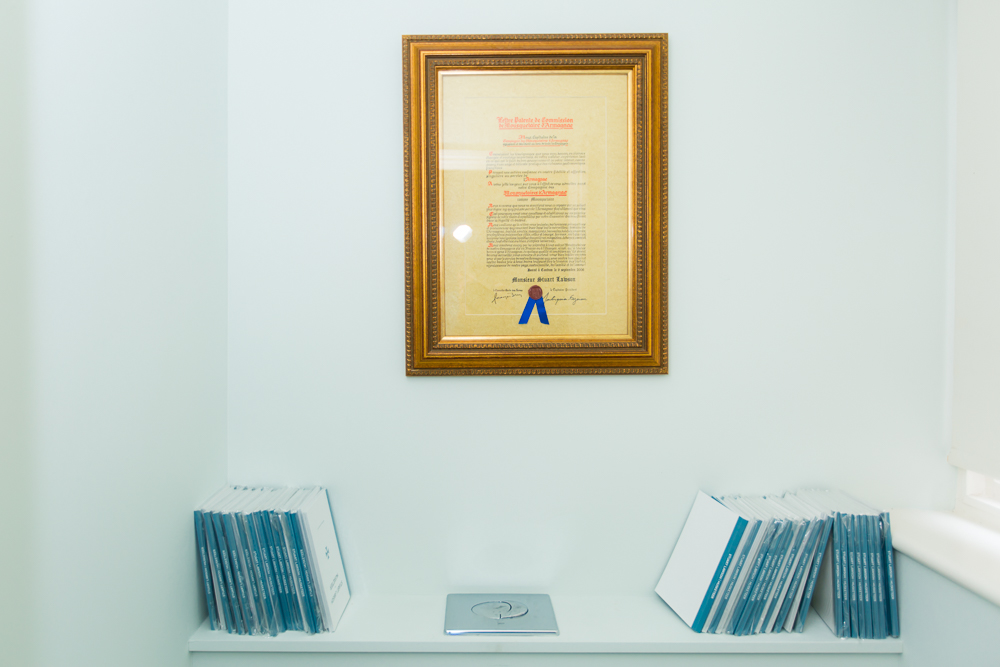

This marked the beginning of Lawson’s relationship with Russia, where between 2005 and 2009 he was named “Best Banker in Russia” four years in a row, an award conferred by representatives of the Russian Ministry of Finance, the Central Bank, the Association of Russian Banks, and the Audit Chamber.

Yet his Russian chapter began less successfully. He had been invited by Sergei Boev, a former manager of a Citi branch in St Petersburg. “I returned not as a director but as an adviser to my former manager, who by then had become head of Delta Bank,” Lawson recalls. “It was difficult to accept that I was no longer making decisions but advising, sometimes watching people make the wrong choices. But I learned that if circumstances change, you must swallow that fact rather than trying to rewind the tape. It won’t work. You cannot drive while looking only in the rear-view mirror. You need to recognise when the past no longer represents the future, and adapt, setting realistic goals for yourself.”

According to Lawson, a full return to a senior role took four years. In 2004 he became head of Soyuz Bank, and in 2008 he assumed the chairmanship of HSBC Russia.

“I would say there is a problem with the concept of ‘successful failure’ in Russia,” he reflects. “Russians do not forgive mistakes, neither their own nor others’. In the West, you can try 500 times, and the 501st will work, because there is an established understanding of risk that ultimately brings benefit. What risk could you take in the USSR? Tell an unsuccessful joke about Stalin? The consequence? Twenty years in Siberia. The concept of trying, failing, and learning is only just emerging. In Russia, the idea of risk is different, more like Russian roulette. That prevents people from learning, progressing, and integrating risk, error, and growth.”

“Sometimes people say that if you constantly adapt, you will lose yourself,” he continues. “In reality, if you are comfortable with yourself, whole, and trustworthy, you do not lose yourself — you learn to respond differently to new circumstances. You remain the same person. And it is important to add: if you make money the goal of life, it will never be enough. After the first million, you want more. Intellectually, working with money is fascinating, but it is only a tool. When the working day ends, or life passes its midpoint, it is a little sad to see people showing off their big houses or fast cars. They are lonely. I have a home, smaller than those of my colleagues, but I have seen, experienced, and achieved so much that I sometimes envy myself.”

“Losing power is difficult,” he says, “but it often helps you understand that true leadership is not a position, but being listened to because you have a vision, not because you have authority. I now manage no one except my dog, yet I have influence, and I have expanded this sphere of my life: I became a senior consultant at EY in Moscow and took up teaching. From next year, I will be a professor at the Graduate School of Management at St Petersburg State University.”

Leave a comment